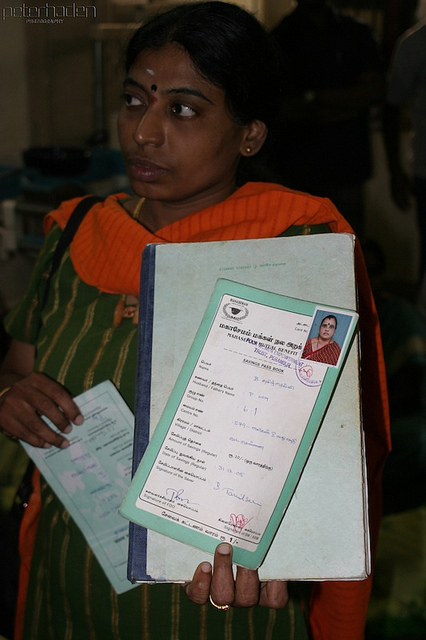

Mrs. Rajalakshmi displays loan cards issued to borrowers enrolled in Mahasemam Trust’s Microfinance Loan Program. Chennai, India.

Over the last few decades, microfinance, or microcredit, has become a popular mechanism for economic development and poverty reduction.

Microcredit can be defined as “programmes that extend small loans to very poor people for self-employment projects that generate income, allowing them to care for themselves and their families”. This “contemporary” idea of microfinance is widely believed to have been created by Mohammad Yunus, who began lending to poor women in Jobra, Bangladesh in the 1970s. He later founded his own microfinance institution (MFI) known as the Grameen Bank. In 2006, Yunus, along with the Grameen Bank, won the Nobel Peace Prize for “their efforts to create economic and social development from below”.

Microfinance, however, is not a new concept; it has played a large role in civil society for centuries and has taken several different forms outside of the modern, formal banking sector. In Latin America, for example, the use of Tandas is the most popular form of saving and financing among poor populations. Tandas are formed among a small group of people who agree to give a specific amount of money to the Tanda every week. The collected money is then given to one of the Tanda members on a rotating basis. Each member will receive the total amount of the Tanda one week during the arrangement. This system has proven to be a popular model for those communities in which “modern” financial services through the banking sector are not available. A good list of the different microfinancing models can be found on the Grameen Bank website.

Why are more “institutional” forms of microfinance unavailable to certain populations?

Microfinance programs are typically considered risky and not financially sustainable to most institutions. Many people interested in microcredit are typically poor families with little capital and little or no credit history. Additionally, microloans typically range from a few dollars to a few hundred dollars, making it hard for finance institutions to make a profit on these programs. Therefore, most finance institutions do not offer these services; they choose to focus on the larger clients, with strong credit history, significant collateral, and who are willing to take out loans of significantly higher principals.

This exclusion of the world’s poor from larger financial institutions creates a void in business and financial development in which microcredit institutions – or small-scale communal practices – work to fill.

These institutions, however, come with their own weaknesses and costs. Due to the low value of these loans and the innate uncertainty of the borrowers, interest rates from microfinance institutions (MFIs) tend to be high:

Administrative Costs

The administrative costs of lending $10,000 to one borrower are not the same as lending $100 to one hundred borrowers. Additionally, MFIs face certain difficulties in screening clients and collecting payments. Many clients of MFIs may not have a credit history on record, may not have collateral, and may be illiterate. MFIs require a significant amount of staff and infrastructure in order to provide their services to customers.

These costs are passed on to the customer:

MFIs calculate interest rates similarly to larger financial institutions. They take into account the cost of the money lent and the cost of default by borrowers. These costs are proportional to the amount of money lent and are priced as a percentage. For example, if a bank determines that these costs amount to an interest rate of 10%, a borrower asking for a one year loan of $100 will pay $10 in interest to the bank. A different borrower asking for a one year loan for $300 will pay $30 in interest to the bank.

However, there is one additional cost to the bank calculated into the “price” of the loan. A transaction fee is added to the loan that covers the administrative costs involved in preparing the loan. This fee is typically a fixed rate for all loans made by the bank, as the amount of time spent preparing a $100 loan is roughly the same as the time required to prepare a $300 loan. So, if the bank charges a transaction fee of $25 to all its clients, the $100 borrower will pay a total of $35 to take out the loan, which equates to 35% of the loan’s value. However, the $300 borrower will pay a total of $55 in order to take out the loan, which only equates to 18% of the loan’s value.

The world’s poorest pay higher rates, proportionally, to borrow money. In 2010, the estimated world average for interest rates and fees was around 37%.

So why provide microcredit? What are the benefits?

In some cases, these high interest rates provided by MFIs are still cheaper than the costs incurred using less formal methods of borrowing. According to CGAP, an independent policy and research center on financial access for the world’s poor, the rates given by MFIs are often “far below what poor people routinely pay to village money-lenders and other informal sources, whose percentage interest rates routinely rise into the hundreds and even the thousands”.

In a paper prepared by UNESCO for the 1997 Microcredit Summit , they state:

Over eight million very poor people, especially women, are benefiting today from different microfinance programmes. Experiences of these programmes show that provision of microcredit and savings facilities, when efficiently utilized, enables the poor to build strong microenterprises, increase their income, and participate in economic growth. It also contributes greatly to the empowerment of the poor, especially women, and helps to raise awareness and aspirations for education, health care and other social services. In light of these achievements, microfinance is increasingly being considered as an important tool for poverty reduction.

The film Microfinance: In Their Own Voices gives real world examples of people who have been positively affected by microcredit loans. It “presents real, personal stories of microfinance clients from different parts of the world, including Kenya, India and the Philippines.” The video, and more information, can be found on the International Year of Microcredit 2005’s website.

How do Microfinance Institutions function?

There are several different models used by microcredit institutions around the world:

The Grameen Bank provides “solidarity group lending” in which prospective borrowers must be part of a lending group in order to receive a loan. Every group member is accountable to, and liable for, all the other members’ loans. In this video, Mohammad Yunus explains how the Grameen Bank began.

Another organization, called Kiva, is an internet platform in which lenders from all over the world can help MFIs lend money to borrowers in another part of the world. In this video, Kiva explains microfinance and their model in a creative and simple cartoon. In this TED Talk, Kiva founder Jessica Jackley explains why she created Kiva.

Some organizations, like Zidisha, do direct peer-to-peer financing in which lenders lend money directly to borrowers through the internet platform. On the website, lenders and borrowers agree on their own interest rates and terms of payment.

Other microfinance NGOs and MFIs working in microfinance include MYC4, Janta (specialized in student microcredit), Accion, BRAC, FINCA, Women’s World Banking, and Opportunity International. There are hundreds of additional organizations currently working in the microfinance sector.

What about other financial services?

Recently, the idea of microfinance has widened to include other products such as microsavings and microinsurance. These services are now being offered by many microfinance institutions in addition to microcredit.

The video below shows how the bank Bancomer in Mexico is working with IDEO to develop sustainable microsavings programs for people with little income. It does a great job at explaining some of the challenges of delivering microfinance services to the poorest populations.

Image Credit: Flickr User: Peter Haden. CC Licensed.